| ||

| Pontormo Deposition from the Cross 1528 |

Mannerism or

Maniera is considered a late style of the sixteenth century.

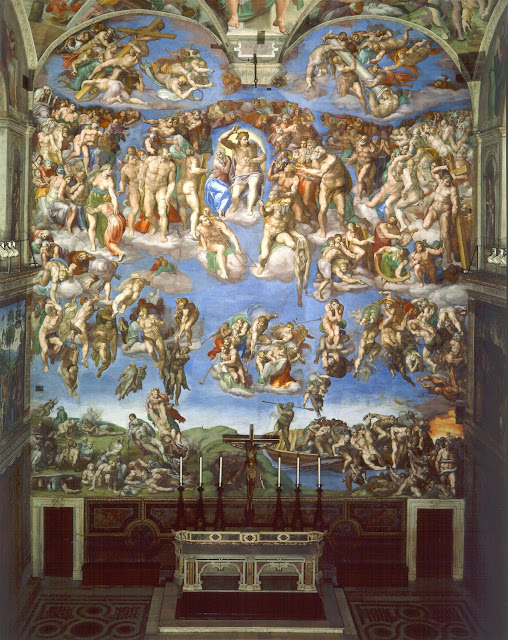

The group of artists working in this way were mainly influenced by

High Renaissance master Michelangelo. “Michelangelo's authority

impressed a sculptural example on Maniera painters, not only in his

works in stone but by his sculpturesque painting” (Freedberg, 287).

Raphael is also considered an influence because "in his last and

most influential years, [took a] sculpturesque cast into his art

[which] tended to dictate a stressed plasticity” (Freedberg, 287).

Artists like Michelangelo influenced mannerists due their

sculpturesque styles (plasticity) as stated by Freedberg “the

hard-surfaced, plastically emphatic form of many high Maniera

pictures, which has so large a part in this effect, comes often from

the deliberate imitation of a sculptural style” (287).

Maniera has "problems" in that it is not drawn from

life or nature. It was after the artist “Raphael [that] there was

suddenly a decline. Artists abandoned the study of nature, corrupted

art with la maniera or, if

you prefer, a fantastic idea based on practice, and not on the

imitation [of nature]” (Smyth, 22). In the “mid-sixteenth

century, painters of [the] day were using the word maniera

derogatorily in connection with

painting in which one saw forms. Faces, and (by implication) bearing

and movements that were almost always alike” (Smyth, 35). It must

be this extreme dislike of the style since it's beginning that it has

become so controversial and no longer included in our History

of Italian Renaissance Art.

Freedberg, in fact, did not like the

term Mannerism or Maniera (but used them anyway), he much preferred

to classify this style of art as "anti-classical". This

makes sense because of the properties of the particular style are

somewhat the antonym to the High Renaissance which was classically

based. Maniera painting has characteristics of sculpturesque

modelings or plasticity, elongated figures, extreme detail, angular

poses, and is created usually by examining other artwork (not

directly from life). “More

pervasive are the principles of angularity and of spotting the

composition with angular elements. Elongation is not central to

maniera, but these two

conventions are” (Smyth, 43). Maniera painters considered

“line, modeling, and color in

painting di maniera [to

be] better suited to serve a uniform ideal than nature's variety”

(Smyth, 49).

However, “Maniera painting

is an art of figures, as most central Italians thought painting

should be” (Smyth, 49). The emphasis on grace and elegance in this

style correlate to the word maniera,

which "has an old association with style" (Smyth, 98). Some

believe mannerism to be a decline in Florence and Rome after 1530 or

1540, the monotonously uniform figures could be easily disregarded.

However, according to Smyth, “not only is Mannerism now considered

valid for the Cinquecento, but it also begins to be applied as the

name for a subjective, surrealistic, anticlassic phenomenon that

critics see recurring in European art.” (Smyth, 98-99)

I

find the work of Mannerism exciting, the strange color schemes and

weird figures are refreshing. I think mannerism is still a style

sought out today. Contemporary artist John Currin must be inspired by

this period of art, as well as the Pop Surrealist movement. Pop

Surrealism correlates to the surrealistic characteristics of

mannerism. I look forward to learning more about mannerism is class,

and if others agree that mannerism is still influential today. Maybe

more influential than the High Renaissance?

|

| Lori Early LEILA oil on board 2007 (Pop Surrealist) |

|

| John Currin The Old Fence 1999 |

|

| John Currin Thanksgiving 2003 |